In a pretrial hearing Tuesday at the Guantánamo Bay military tribunal, Clive Stafford Smith, a lawyer for a potential witness in the war crimes case, accused government prosecutors of “outrageous” misconduct.

During the hearing for the case of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, who is charged with masterminding the October 2000 attack on the USS Cole, Stafford Smith said the government attorneys had failed to release exculpatory information about Nashiri and made false statements in the course of their failure.

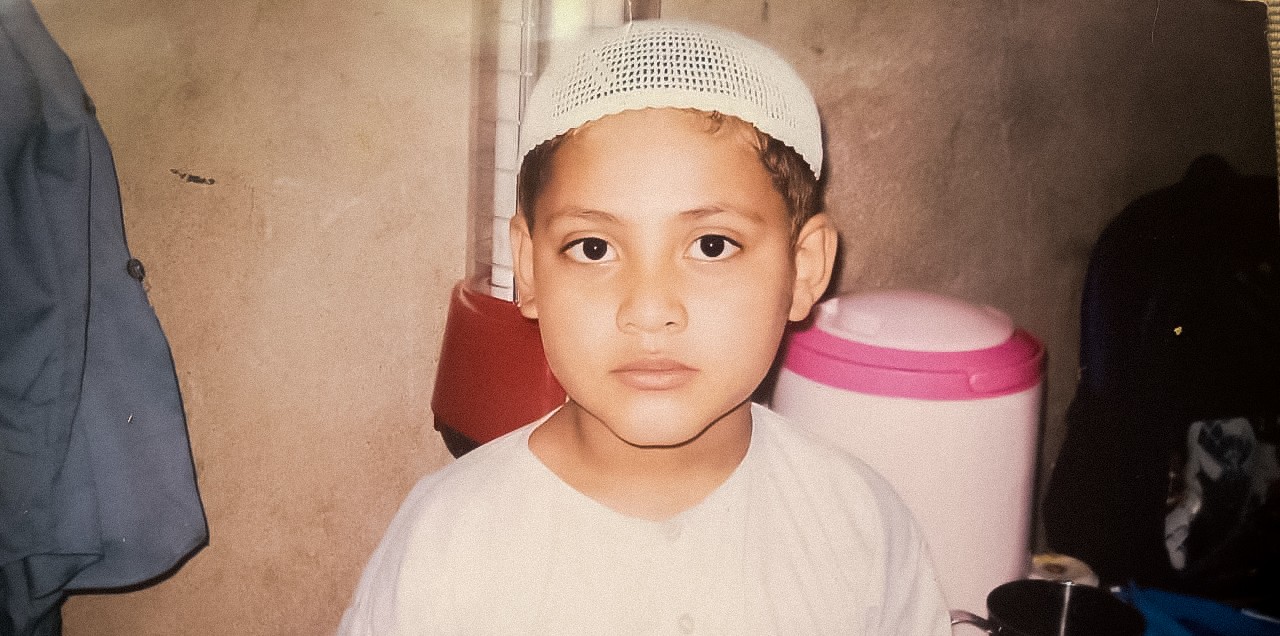

Stafford Smith, the lead counsel for Ahmed Rabbani, a former Guantánamo detainee who was tortured by the CIA, made the allegations after being called to the witness stand by Nashiri’s defense team.

“I’ve never, ever, in 40 years reported someone to the bar before this case.”

Stafford Smith testified that the prosecutors had filed a brief that falsely said Rabbani had not recanted his initial testimony because, Rabbani said, it was made under torture. After raising the omission, Stafford Smith said, he felt it was not getting due attention and took the unusual step of reporting the prosecutors to their state bar associations.

“I’ve never, ever, in 40 years reported someone to the bar before this case,” Stafford Smith said in court. “I don’t like doing that, but I felt I was required to.”

In the court motion last year that set off Stafford Smith’s ethics complaints, the Guantánamo prosecutors said they had no knowledge of Rabbani’s recantation or claims the testimony in question were extracted by torture. (The chief prosecutor’s office declined to comment for this story.)

Stafford Smith and Kristin Davis, another attorney from Rabbani’s legal team, told the court that, in the 2018 and 2019 “proffer sessions” to negotiate Rabbani’s release from Guantánamo, the detainee recanted his past testimony, which he told government investigators he made under torture.

The recantation should have been recorded and made available to Nashiri’s defense team under the Brady rule, which mandates the release of exculpatory evidence. A court filing by the prosecution in 2023 showed that this never happened.

Nashiri’s lawyer, Anthony Natale, said in an interview before this week’s court hearing that the prosecutors’ alleged falsehoods and failures to hand over exculpatory materials were indicative of why the Guantánamo military commissions have foundered, yielding no convictions at trial since their creation nearly a quarter century ago.

“The situation,” Natale told The Intercept, “is one of many where the government’s abandonment of our constitutional principles resulted in injustice and delay.”

Recantation

Stafford Smith’s 2023 bar complaints were set in motion by the negotiations five years earlier over Rabbani’s release. Stafford Smith and Davis had agreed to allow Rabbani to cooperate with the FBI in Nashiri’s prosecution in a bid to expedite their client’s release.

In the “proffer session,” the government wanted Rabbani to confirm incriminating statements made in the early 2000s against Nashiri. It was understood among Guantánamo detainees, Rabbani told The Intercept in an interview, that giving testimony about other detainees could help facilitate an early exit from the prison camp.

He said he had seen it happen before, with former Guantánamo detainee, Ahmed al-Darbi, who was repatriated to Saudi Arabia in 2018. Darbi — who was, like Rabbani, identified as a victim of torture by the Senate Intelligence Committee’s 2014 report on abuses during CIA terror investigations — had been offered the option to testify against Nashiri and took the deal.

That testimony from Darbi, however, was also false, according to Rabbani’s account of conversations with Darbi before either was released from Guantánamo. In the prison, Rabbani had confronted Darbi about falsehoods concerning Nashiri.

“When I scolded him, he responded that he wanted to get out no matter the price,” Rabbani told The Intercept. “I told him that he is involving al-Nashiri in things the latter hadn’t done — and you save yourself, leaving him behind in his predicament that wasn’t of his making.”

“He responded that he wanted to get out no matter the price.”

Darbi, Rabbani said, expressed contrition: “He showed remorse when it was too late.” (Darbi, who pleaded guilty in 2017 to a role in a 2002 Al Qaeda bombing of a French oil tanker, is currently serving his prison sentence in Saudi Arabia and cannot be reached for comment.)

In 2018, Rabbani’s attorneys were seeking a deal like the one that got Darbi out of Guantánamo, Stafford Smith said in court, but he had cautioned his client not to perjure himself. Rabbani, unlike Darbi, had never been charged with a crime.

Rabbani told The Intercept that, during his interviews with the FBI in 2018 or 2019, he recanted his past statements about Nashiri. Rabbani said he repeatedly raised his torture to the FBI agents and attributed his statements about Nashiri to the torture. Davis confirmed in court Tuesday that Rabbani refused to confirm his past allegations because they were made under torture.

Five years later, the Guantánamo prosecutors announced that they still planned to solicit testimony from Rabbani and potentially call him as a witness. In January 2023, prosecutors filed a pleading claiming they had no knowledge of Rabbani giving exculpatory information about Nashiri.

“The Prosecution has found no information that during the proffer sessions either detainee recanted prior statements or that they made additional allegations their prior statements implicating the Accused were the product of or result of torture,” the pleading says, referencing Rabbani and a second detainee whose statements against Nashiri had come into question.

The prosecutors’ claims of ignorance got under Stafford Smith’s skin. In late February, according to a emails obtained by The Intercept, he wrote to Navy Rear Adm. Aaron Rugh, the head of the prosecution team, alleging that the pleading contained false statements and requesting the signatories’ bar numbers. Rugh responded that he would investigate the matter but did not send the lawyers’ information. (In response to a request for comment, Rugh’s office said, “When matters are pending litigation, it would be inappropriate for the Department of Defense to comment.”)

Stafford Smith found seven of the nine lawyers’ bar numbers and reported them. Six of the complaints use nearly identical language, with slight differences in the introductions and occasional added specifics. A seventh, made later, contains more information and additional allegations. For all but one of the prosecutors, their state bar associations list no public record of discipline; one of the prosecutors has a grievance case listed, but no resolution.

“You certainly understand how serious it would need to be to report someone to the bar?” a prosecutor asked Stafford Smith at the hearing Tuesday.

Stafford Smith replied, “I do, absolutely.”

Torture Testimony

The CIA tortured Rabbani for more than 540 days, according to the Senate torture report. The torture included a stint in a covert American black site in Afghanistan.

Rabbani has described being held in complete darkness for long periods and being subjected to a medieval torture technique known as “strappado”: hanging someone by their bound arms and suddenly dropping them.

Recounting his ordeal later, Rabbani said he gave incriminating statements about Nashiri sometime between 2002 and 2004 while at the black site.

Last August, the Nashiri case at Guantánamo’s military commission was shaken up when the then-judge said an early confession by Nashiri was inadmissible because it was extracted through torture. The ruling dealt a blow to the government’s longest-running death penalty case under the military commissions.

Testimony at the commission hearing on Tuesday, however, indicates that the government’s quest to use evidence obtained through torture from other detainees was well underway when the judge made his decision on Nashiri’s confession — and that the pursuit of torture testimony continues into the present.

Rabbani said that the attempts to use his testimony speaks to a failure to reckon with Guantánamo, torture, and the other excesses of the U.S. campaign against terrorism.

“America does not want to admit the bitter truth of their failure in investigations,” he told The Intercept, “and the practice of injustice and torture that is internationally prohibited.”