In March 2003, in a secret CIA prison cell in Poland, a small frog jumped out of a drain and an interrogator caught it.

“No, no,” said Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the accused architect of the 9/11 attacks. “Let it stay.” He asked that the frog be returned to the drain.

Later that day, an unnamed observer included the incident in a CIA cable addressed to “IMMEDIATE DIRECTOR,” calling it “a poignant moment.”

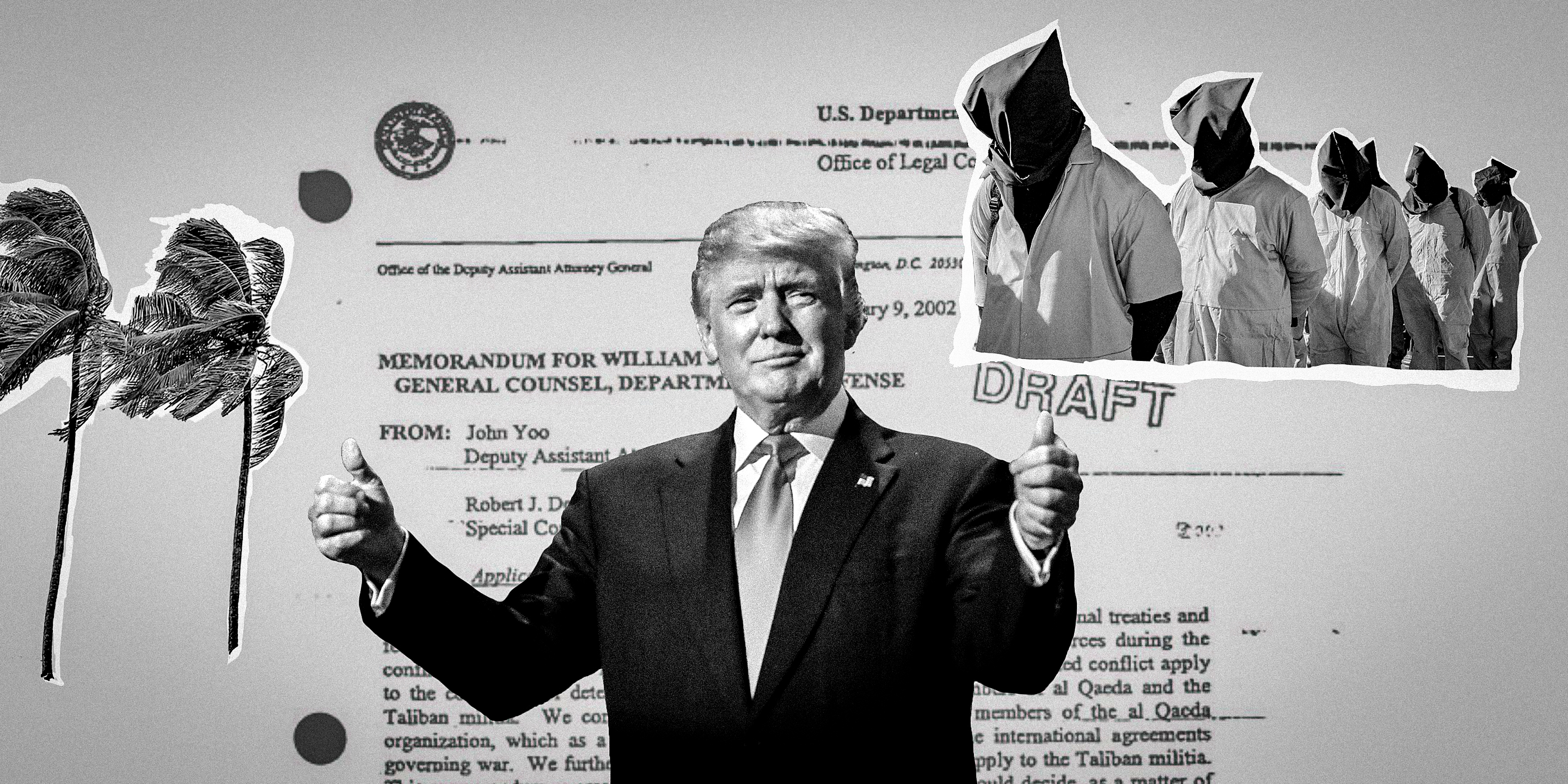

The CIA interrogation program has been well documented. But recently declassified cables, published here for the first time, reveal in new detail interrogators’ attempts to transform detainees into collaborators in the war against Al Qaeda.

The cables chronicle the banal and brutal moments of Mohammed’s so-called enhanced interrogation over a period of almost four weeks in 2003. They display in cold bureaucratic prose the thinking behind torture tactics, including waterboarding, “walling,” and sleep deprivation. And they exhibit a committed belief that enhanced measures always move detainees closer to an imagined breaking point that, once met, force them to produce more accurate information — a belief that the 2014 Senate torture report showed to have been wrong.

“Keep pushing,” a cable urges, “until [Mohammed] reaches his resistance limit, and then exploit his weakness when it occurs.”

The cables were obtained in a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit for records on the interaction between detainees and interrogators Drs. James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, two contract psychologists who formed a company that was ultimately paid about $81 million to develop and execute the CIA program after 9/11. In May, Mitchell and Jessen were called to testify before a military tribunal trying Mohammed and four other alleged 9/11 planners held in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. If they testify — which Mitchell could do as soon as this month — it will be the first time that the pair are forced to discuss their techniques in a criminal case.

This week, in a military courtroom in Guantánamo Bay, a judge is hearing motions in the case against Mohammed and his four alleged 9/11 co-conspirators. Evidence gathered during Mohammed’s CIA interrogations cannot be used in his trial, which is scheduled to begin in January 2021. Now, a key issue for Mohammed’s defense attorneys is whether information gleaned during FBI interrogations that followed his time at CIA black sites was also tainted by his torture.

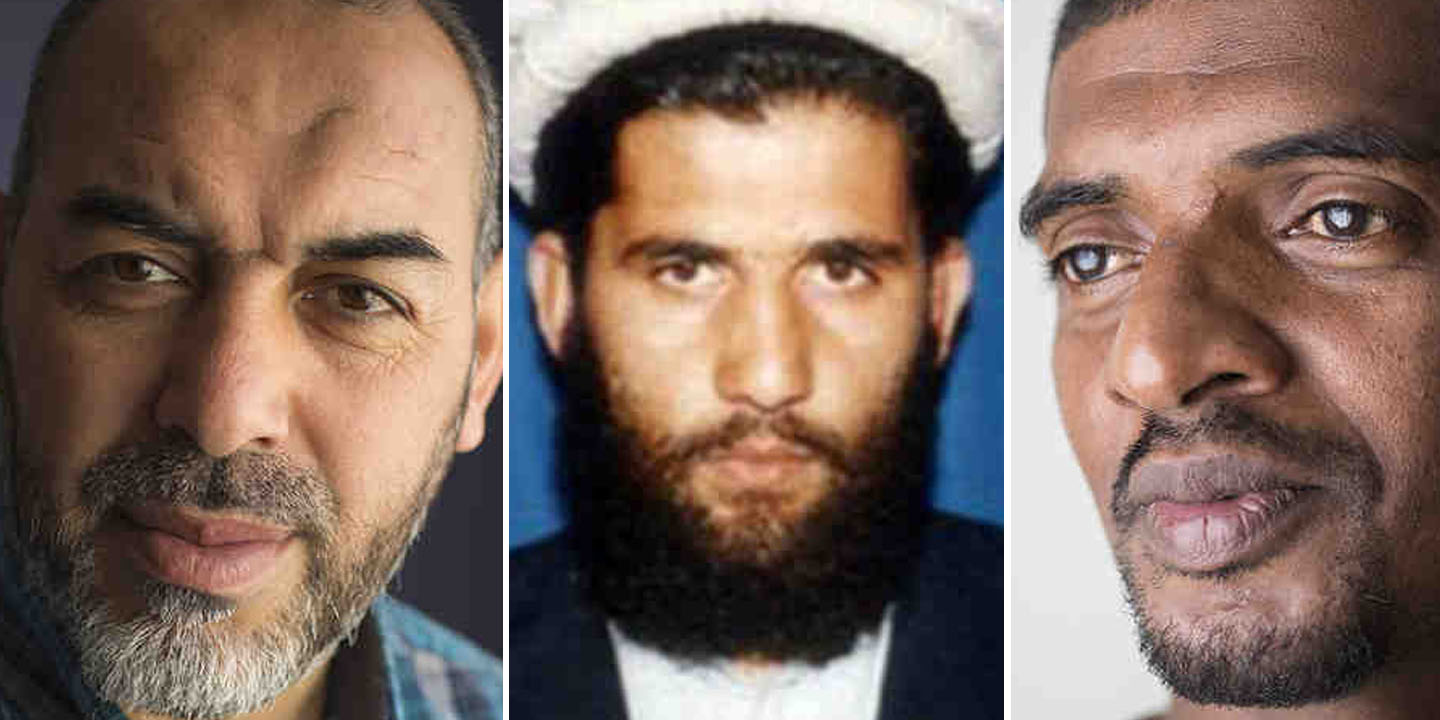

In 2005, Jose Rodriguez, head of the CIA’s National Clandestine Service, ordered the destruction of 92 videotapes showing the enhanced interrogation of detainees Abu Zubaydah and alleged USS Cole bomber Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri. With the tapes gone, the cables about Mohammed’s enhanced interrogation constitute one of the few public real-time records to extensively narrate what happened to a “high-value” 9/11 detainee inside an interrogation room.

The cables, some heavily redacted, confirm many findings of the Senate’s torture report. Mitchell, who interrogated Mohammed, criticized the report in his memoir, “Enhanced Interrogation,” writing that neither the report nor its accompanying documents “put you in the room with the action so you get a sense of what was actually going on and why. That’s what I intend to do.”

But Mitchell’s book mostly dodged the agony inside the interrogation room. The cables published here do not.

“We Should Not Rule Out Any Method”

In July 2002, Abu Zubaydah, the CIA’s first detainee, was being held in isolation, while the George W. Bush administration determined the legality of coercive tactics. Several weeks earlier, interrogators believed Zubaydah had provided a “revelation” not detailed in the cables. Since then, however, Zubaydah had achieved a series of perceived “victories” that bolstered his “resolve and resistance strategy, thus decreasing the long-term overall effectiveness of the interrogations,” a cable states.

Interrogators concluded that “we must act in a way outside AZ’s expectations and follow through on our threats. Until this point in the interrogations, we have made several threats to AZ while implementing the ‘bad guy’ role,” the cable states. “While the first of these threats facilitated the 19 May ‘revelation,’ each subsequent episode lacked the promised repercussions, a fact that was not lost on AZ.” Enhanced measures were coming.

The CIA’s Legal Group, Counterterrorist Center, identified in the documents as “CTC/LGL,” has “emphasized that we should not/not rule out any method of interrogation whatsoever,” the cable explains, but adds that headquarters “will need to document in advance the legal analysis for such methods, to ensure that our officers are protected.” If the black site team wanted to employ specific enhanced measures that they suspected might not be permitted, they planned to ask then-director of the CIA George Tenet to obtain a formal declination of prosecution from then-Attorney General John Ashcroft.

“In short,” the cable concludes, “rule out nothing whatsoever that you believe may be effective; rather, come on back and we will get you the approvals. CTC/LGL officers remain available 24/7 to ensure immediate assistance and documentation on any proposals. … We lawfully may employ methods that even the Israelis may not.”

The Waterboard

The interrogators were convinced that they knew when Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was lying.

“When providing answers that were probably truthful, KSM continued his behavior of speaking in a conversational and casual manner,” a March 27, 2003 cable states. “When apparently lying or withholding, KSM continued his earlier pattern of looking down, slowing his answers and speaking pattern, and frequently burping nervously.”

Mohammed lied to his interrogators and, according to the Senate report, the CIA did not always know it. Sometimes, he may also have told the truth.

On March 13, 2003, Mohammed was resigned and anxious, according to one cable. A medical officer had approved “upgraded enhanced measures”: erratic water pours of varying rhythm, timing, and intensity to make the simulated drowning less predictable and more distressing. The fourth session began at 8:40 a.m. and ended nearly an hour later.

“What is the next target in the U.S.?” an interrogator asked.

There was no next target, Mohammed said.

“Subject moaned and blubbered” in between pours, an unnamed psychologist observed.

“What is the plan?” the interrogator asked. “Who are the people? Where are they? What do you have in the U.S.?”

To resist waterboarding, Mohammed held his breath, swallowed water, and, according to a cable, blocked his posterior nasopharynx, a throat cavity behind the nose, letting water run into his nose and out of his mouth. It was a “magic trick,” Mitchell wrote in his memoir. “I was so impressed with how little the reality of being waterboarded seemed to upset him.”

The cables tell a different story.

Enhanced measures were designed to move Mohammed “toward a feeling of helplessness and hopelessness,” a cable states. Rather than engage in a battle of wills with the detainee, interrogators wanted to set Mohammed’s will against itself in a losing battle. Typically during waterboarding, detainees would fail to manage their breathing and emotions. They panicked. They lost. The CIA psychologists called this progress.

However, at times, the cables depict a power struggle between the interrogators and their subject. Mohammed can end the waterboarding. He can talk, but he does not talk. He defeated the waterboard, a proxy for the interrogator, reframing the interrogation not as a rigged test of his own failing will, but as a battle in which a small victory is temporarily possible.

It was an escalating contest. At least once, Mohammed pointed his two index fingers upward as a water pour reached its time limit, which was 40 seconds, according to a 2002 memo from the Department of Justice. In response, interrogators stopped signaling the beginning and end of a pour. Water was redirected “to and around his mouth movements.”

Interrogators believed that “wearing down” Mohammed required erratic “but relatively frequent sessions.” Days later, according to another cable, Mohammed’s “dread of the waterboard has increased so that he whimpers and pleads whenever it is threatened.”

On or around March 18, interrogators made Mohammed choose between the waterboard and sleep deprivation. “Subject immediately turned away from his cell door and appropriately positioned himself in the middle of the room for ‘standing sleep deprivation,’” a cable notes.

Sleep Deprivation

On March 23, at 9 p.m., Mohammed had been subjected to sleep deprivation tactics for 132 hours. He spent most of that time standing, his wrists shackled at or above his head.

He was “only a man,” he had told his interrogators philosophically, “and men break.”

That day, at 30-minute intervals, interrogators entered his cell and demanded information.

“Nothing new,” Mohammed said. At times, he turned “slowly to allow his entire body to be doused” with water “as instructed,” a cable states.

“If I don’t break tomorrow, it will be the next day,” Mohammed told his interrogators.

By March 25, Mohammed was closer to “automatic conformity,” according to a later cable. He wrote and wrote, filling 20 pages. He was finally allowed to sleep, albeit naked and shackled on the floor. After about three weeks and four days, his enhanced interrogation was over.

The Senate report does not explain why Mohammed’s enhanced interrogation ended. But the cables suggest that interrogators thought that Mohammed had entered a new, more compliant phase. “As anticipated, today was a pivotal day for KSM,” a psychologist noted on March 25.

“KSM remains attentive and responsive,” an April assessment states. “He continues to volunteer relevant spontaneous and unsolicited information. His conditioning becomes more effective each day in terms of desired automatic conformity to debriefing preparations as well as his judged level of engagement in the ensuing debriefing dialogue.”

That same month, Mohammed asked how his interrogator viewed his level of cooperation. On a scale of 1 to 100 (with 1 being completely dishonest), KSM registered about 50 or 60, an interrogator said.

This evaluation “distressed” Mohammed, who said “he had something more to tell,” a cable states. He began, in a low, solemn tone, the story of American Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, who had been kidnapped and beheaded in Pakistan. Mohammed claimed that he had murdered Pearl, offering the confession as evidence that he was “truthful about everything.”

The interrogation team cabled that it “remains vigilant,” believing that Mohammed maintained “some level of deception.” But the team also wrote that Mohammed was not “identifiably” engaging “in overt behaviors of calculated or obvious resistance.”

Out of the Shadows

In April 2008, the CIA program ended, according to the Senate report. But the argument over its utility continued. Former CIA officials wrote op-eds, debated on TV, and published books defending the program. Mitchell wrote his memoir.

“The few of us who were present cannot let others distort history,” Mitchell wrote, criticizing the Senate report and news articles on the interrogation program. Yet he supported Rodriguez’s decision to destroy history — the interrogation tapes — saying, “The bad guys could see us.”

During the 18th century Enlightenment, the idea of universal human rights, fueled by new thinking about the autonomy of the human body, contributed to campaigns to abolish torture, historian Lynn Hunt argues. Making torture taboo helped drive it out of the public square and, eventually, into CIA black sites, where “clean” torture — the kind that left no physical marks — was inflicted.

The CIA redacts its officers’ names. The cables do not show exactly who did what and when. But they make more visible a previously hidden experience. The cables reveal Mohammed and his interrogators, dragging torture into the light.